Bryan Batty is the Director of Product and Infrastructure Security at Bloomberg Industry Group, a subsidiary of Bloomberg L.P., the news organization and the Bloomberg terminal. Bloomberg’s focus is on legal, tax, and accounting news, and tax and accounting software.

Bryan Batty is the Director of Product and Infrastructure Security at Bloomberg Industry Group, a subsidiary of Bloomberg L.P., the news organization and the Bloomberg terminal. Bloomberg’s focus is on legal, tax, and accounting news, and tax and accounting software.

Batty runs the product security and infrastructure security teams, working closely with developers and the infrastructure teams to make sure that what is being put into production, and into operations, is done in a secure manner, including looking for existing vulnerabilities within their existing infrastructure.

We caught up with Bryan in January to talk about the process of software development at Bloomberg, and specifically, the management of their software supply chain, in this four part conversation. This is Part One.

Bryan Batty:"If you start out with a tool like Sonatype’s Nexus Lifecycle, it's going to work out well. You’ll know immediately the version of a component, whether it has a license that you want to use, or if it has known vulnerabilities. Nexus Lifecycle knows which component versions are free from known vulnerabilities, and when security issues are discovered, it knows what the vulnerabilities are." -- Bryan Batty

I got my bachelor's degree in 2006, and wanted to be a developer, to build stuff. I really enjoyed it. If security hadn't come along and grabbed me, I would still be very happy building new software and tools. I got into security very shortly after I started in my career. I was attending a Microsoft conference and there was a session on SQL injection. I was just shocked at how easy it was to do that.

So after my jaw dropped, I thought about the code that I had been writing. I said, "Oh, I better go back and fix it." I hacked myself and saw, "Yeah, this code is crap." It was easy to do that back then. Easy to exploit, easy to fix.

Defining Security Requirements

Mark Miller:

SQL injection is still one of the OWASP Top 10.

Bryan Batty:

Yeah, that's crazy. It's been an OWASP Top 10 for ten years, right? One of the originals. It's amazing how new developers still use it... I think it's probably an awareness and education thing. New developers, like I was, just want to make stuff work. We’re given a story to write and say, "Okay, I can build that."

The definition of done should have security requirements, but they often don't, because security is not invited to the table. The definition of done is being creative. Often the developer says, "Okay, as soon as it works, then I'm done." Not all developers are like that. Some are very vigilant about making sure things are done in a scalable way, in a secure way, in a sustainable way.

Mark Miller:

The OWASP Top 10 includes A9, which is “Using Components with Known Vulnerabilities”. How does your team handle that?

Software Composition Analysis

Bryan Batty:

That was something that came up two jobs ago. I was trying to implement an OWASP dependency check. The terminology has changed a little bit. I think over the last couple of years that the phrase has become “Software Composition Analysis” [SCA] for scanning third party libraries, open source libraries for license violations, and for known security vulnerabilities. Among other things SCA needs to review is code quality and age of the library that you're using.

Having used Software Composition Analysis tools for a while we realized how much pushback we get from developers, and how difficult it can be, if the library is very old and they need to upgrade through 30 different versions. Developers are afraid that something's going to break. That goes back to the original Dev and Ops conflict between developers and operations.

For developers, their goal is to push new features into production. They are introducing change into production. For Ops, they want uptime and reliability. They don't want change. When something is working, they don't want new features in production.

For security, it’s a similar thing. If we ask for something to change, developers are suddenly saying, "No, the code works." They're taking the opposite position from security, saying “We don't want to change our code because it works now. We don't know what's going to break if we make any updates.”

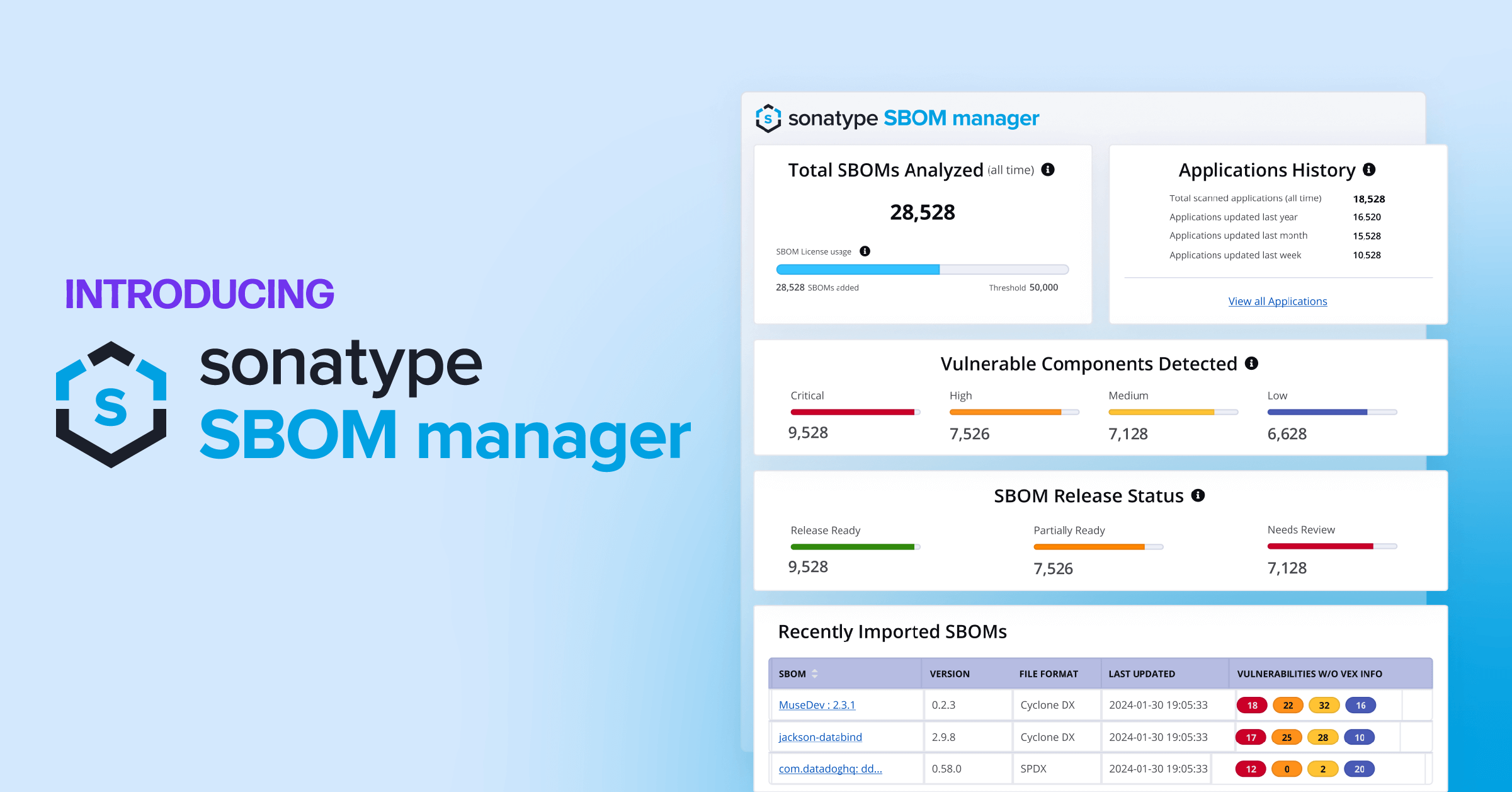

I think for a greenfield project, if you start out with a tool like Sonatype’s Nexus Lifecycle, it's going to work out well. You’ll know immediately the version of a component, whether it has a license that you want to use, or if it has known vulnerabilities. Nexus Lifecycle knows which component versions are free from known vulnerabilities, and when security issues are discovered, it knows what the vulnerabilities are.

When it comes to legacy applications, I’ve had to say, "Okay, I convinced the developers to let me do a proof of concept. Let me run a scan of all of your third party libraries”. Then we find that there are 53 critical vulnerabilities, 200 “highs” and 700 “mediums”. You almost become paralyzed. I almost became paralyzed. What do I do? Where do I start? With that many criticals, start with the criticals. But there are 55 criticals, so...

Strengthening the Software Supply Chain

Mark Miller:

Walk us through that process. You've got 55 criticals. Where do you start?

Bryan Batty:

Not all criticals are equal, right? We analyze the software from that perspective. What Software Composition Analysis tools do is scan the third party libraries. What they don't do is scan your custom code. So one of the biggest pushback I get from developers is “well, if you read through it says this component is vulnerable if you're only calling method X. But we're not using method X, so therefore it's a false positive.” That's what we hear from developers.

I agree that it's not as critical a vulnerability if the code right now is not calling that vulnerable method, but I would not classify it as a false positive. It's not a false positive. It's a vulnerability of the open source software component that you're using.

We try to customize the component and lower the vulnerability. By lowering the likelihood of exploitation, because it's not being called, the criticality will lower, too. If it is a component scored as “critical”, this re-classification based on our research might lower it to a “medium”, or even a “low”. We also take a look to see if it is an internal application versus an external one.

Evolution of Open Source Component Use

Mark Miller:

I don't think developers realize that 80% of a new application is open source components and the source code is basically the glue that's holding those together.

Bryan Batty:

My developers do, they know that, but only after I've told them time and time again.

Mark Miller:

You've been in this awhile now, over 12 years. How has that change affected you? It used to be everybody was concerned about custom source code. Has it shifted to concern about open source software components?

Bryan Batty:

If you talk to the business side, the people who are coming up with new features to put into production, to get market share, to differentiate ourselves from our competitors... they don't care how it's built. They just want it built, they want it built fast. So they have fully embraced open source software as a means of not reinventing the wheel, of being able to utilize what's already out there.

If it takes a developer four hours to integrate an open source library and get it working versus three months of building it yourself -- I'm just throwing these numbers out there -- then hey, great, use the open source library. The attitude is, “I don't care how secure it is or unsecure is. Just use it so we can move on to a bunch of other features.”

They have fully embraced open source software. The onus is on me to educate them of the dangers, the risks, of using certain libraries, and how vigilant you have to be staying up-to-date on libraries. Not to mention ensuring that we're not violating our license policy and that we're using secure libraries.

Mark Miller:

With certain kinds of licenses, if you add something to the software you have to give it back to the community. How is your team monitoring that? What do you do?

Bryan Batty:

Now we're using Nexus Lifecycle, a product that helps us out a lot. I am able to scan any open source component for license violations. More importantly, I can show people, “hey this component’s license was in violation and here's what we need to do to... you need to either swap it out or license it out.”

This is Part One of our conversation with Bryan Batty. In Part Two he discusses building security into an application from the start. In Part Three he explains his views on experimentation and measuring success. Finally, in Part Four, he shares why he selected the Sonatype Platform.