Cyber insurance isn’t a topic I normally talk about. But, as I’ve become even more focused on the software liability space and the ever-growing new regulations aimed at protecting software supply chains, my curiosity about the world of cyber or cybersecurity insurance was piqued.

As I’ve learned more, it’s become obvious that we’re heading down an extremely tough and dangerous path. One in which cybersecurity liability insurance is becoming a moral hazard and a potential problem of economic proportions.

What is cyber insurance?

So we’re on the same page about what I’m talking about, let’s define a few things. Just like auto, home, or flood insurance, cyber insurance is meant to protect and safeguard businesses in the wake of a digital attack or cybersecurity event. It started becoming popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s as part of the “dot-com” bubble. With so many people taking to the digital world, businesses quickly saw the risk associated with their new online presence.

Over the years, what cyber insurance covered or didn’t cover changed just as much as the internet did. Specifically for the US market. In 2003, California passed the Security Breach and Information Act, which said that if you were doing business in the State of California, organizations had to alert residents of any data breach by an unauthorized party. Other states quickly followed suit, which inherently changed the game for cyber insurance and created the need for first-party expenses and third-party liability insurance.

Rising tides and decrease in coverage of cyber insurance

Fast forward to the 2010s and now the early 2020s, and the number of breaches as well as the variety and sophistication of cyber attacks has drastically changed. As we learned, dissecting the new wave of software liability, case law, regulations, and increasingly, governments are looking to place sole responsibility on the organization to ensure their products are safe for end users. You can read more about how cybersecurity liability is evolving here.

This is important, because if organizations suddenly face a new era of liability based on the software they ship, it’s natural to expect they will respond by seeking insurance. But, as the shifting landscape of cyber attacks stands today, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to insure and protect business assets from the growing complexity of cyber threats.

There are a variety of things bringing cyber liability insurance providers to their knees:

- Phishing

- Ransomware

- Spyware

- Simple insecure passwords

- Vulnerabilities

- Software supply chain attacks

According to IBM, the average cost of a data breach in the US is $9.44 million. With hundreds of thousands of breaches a year being reported, it’s outrageously costly to insure.

Understandably, insurance companies pass on the increasing costs to the businesses they protect. According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, direct-written premiums collected by the largest US insurance carriers in 2021 increased by 92% YoY. Article after article is coming out about the “rise in premiums” or “rising cost” of cyber insurance. As detrimental as rising costs can be, it still means there is a marketplace of insurers willing to take on risk and mitigate damages with businesses - albeit with a number of caveats.

An even more significant concern is starting to arise as large institutions question their ability to provide insurance - and still make a profit. In early February 2023, The Financial Times reported that for nearly the first time ever, Lloyd’s of London, who has previously touted its ability to put a price on anything, said it will not insure “systemic cyber risk, or the type of major, catastrophic disruption caused by state-backed cyber warfare.” The article reasons that while typically, acts of war are not part of insurance coverage, it raises numerous questions about the industry’s ability to provide appropriate protection.

Similarly, the CEO of Zurich, Mario Greco, made a bold statement that cyber, not systemic risks from natural disasters or the pandemic, will be the industry that becomes uninsurable. He postures, “What if someone takes control of vital parts of our infrastructure, the consequences of that?” For a large-scale attack impacting a vast network of different services like hospitals, police, and fire/rescue, the potential for casualties and the associated liability of the organization that produced the compromised system could represent catastrophic financial loss.

A flood of economic proportions

Let’s circle back to flood insurance for a moment. If you don’t live in the US, or own property in a state like Florida, you may not realize exactly how flood insurance works when you live in an area prone to seasonal storms that cause, well, lots of flooding. In short, private insurance companies won’t touch it. It’s simply too costly and not worth it for them.

So, to provide flood-prone areas with some form of insurance, the government has become the insurer of last resort, providing property owners, renters, and businesses with flood insurance, often through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). In Florida specifically, the state insurer has more policies than any other insurance company. This is a combination of insurance companies pulling out and rates that rose more than 39% above the average. The increase in cost is mostly because Florida has about 75% of loss claims related to hurricanes, which are increasingly causing not only isolated catastrophic disruption due to high winds, but rising sea levels and inland flooding.

As detailed in “Moral Hazard and The National Flood Insurance Program” by Mary Mcgee, for all practical purposes, NFIP and similar programs have become the sole providers of flood insurance for homeowners and small businesses.

She highlights that in creating the program, the government had three goals:

- Identify flood risk areas across the country.

- Minimize the economic impact of flood events using floodplain management.

- Provide affordable flood insurance to individuals and businesses.

However, the only way to accomplish this was to subsidize flood insurance to the point that policyholders pay 10% of the actual insurance cost. A great deal for the homeowners and businesses, a really tough deal for the government. As a result, these subsidized rates have unintentionally encouraged people to live in vulnerable flood prone areas, creating a moral hazard problem. By providing incentives to stay and saying the government will keep giving you money to rebuild every time a hurricane damages your house. The risky behavior (living in a flood zone) continues without enough precautions put in place.

We’re getting increasingly closer to this imbalanced situation with cyber insurance.

As cyber liability insurance becomes harder to come by, US agencies are already looking at what becoming an insurer itself would look like. At the end of 2022, the US Treasury Department requested public input on a potential federal cyber insurance program, highlighting a coverage gap for US companies as insurers reduce offerings.

The Federal Spending Bill passed just before 2023 directed the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to:

- Research and report on the feasibility of a public-private ‘cyber insurance and data analysis’ working group.

- Establish an accreditation program for third-party cybersecurity providers.

- Have that accreditation program work with federal agencies, critical infrastructure operators, and local governments.

Storm watch ahead

Knowing what we know about flood insurance - we could be headed toward a dangerous situation when it comes to cybersecurity. If companies know they are “covered” and at a low, subsidized rate, we would lose one of the most important incentives currently leading to real cybersecurity change - money. Remember, the average cost of a data breach in the US is $9.44 million. If a multi-billion dollar organization only has to worry about a fraction of that, what’s encouraging them to follow cybersecurity best practices?

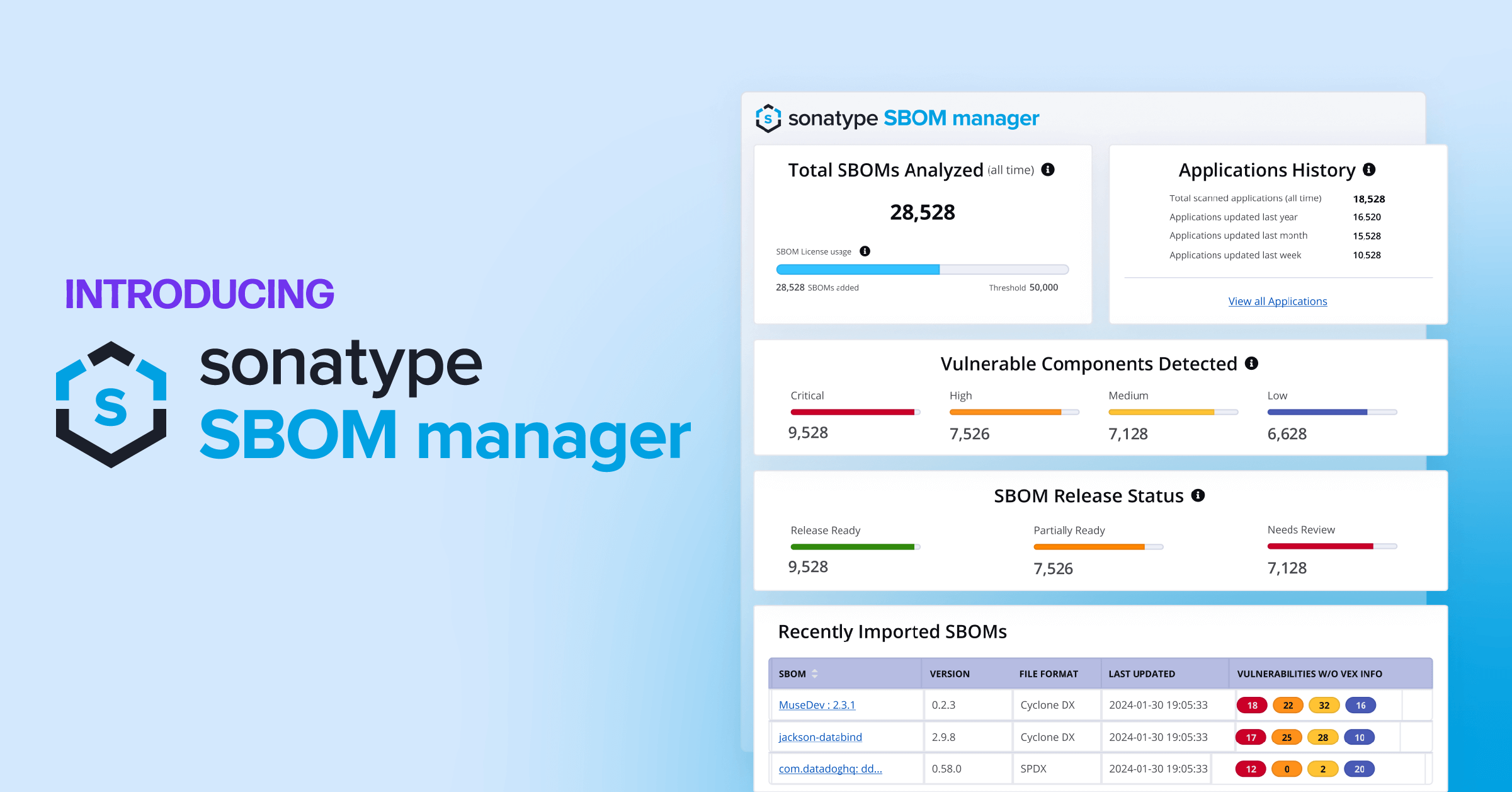

Unlike flood insurance, there are things we can do to mitigate some of these issues. Just in the software supply chain and open source world, we talk about four principles that can help with this:

- Use better and fewer open source projects.

- Use high quality components from those projects.

- Fix vulnerabilities or code quality issues at the beginning, and never pass them farther into the SDLC.

- Create transparency with SBOMs that you continuously monitor.

So, how can you take action and implement the recommendations above?

First, Sonatype has created solutions to help with these principles (we believe they’re the best in many ways). Our tools are built to integrate with your existing processes and enable you to adopt the best practices above.

At the same time, cybersecurity is vast. While our tools will help mitigate the downstream effects of using vulnerable open source components, this tooling is far from the only thing enterprises should invest in.

Many other solutions should be considered to create a defense in depth cybersecurity approach to protect your organization - but if we all work together, we can stop cyber breaches in a way we can’t stop hurricanes.

I don’t have all the answers. But, I have to wonder - are we doing a disservice by offering a similar federal cyber insurance program? Does this then mean businesses won’t focus on creating real change in how they do things? Should we adjust our behaviors? There are many questions to be asked - and answered - to ensure calmer waters ahead.

.jpg)