We are just halfway through 2021, and we have already seen an exceptional increase in open source malware and novel software supply chain attacks. And, they seem to just keep coming.

I'm talking about a persistent pattern demonstrated by threat actors infiltrating upstream code repositories in one way or another.

Below are just a fraction of some of the recent, real-world software supply chain incidents that caused havoc:

- The Kaseya ransomware incident, encrypting the files of over 1,500 businesses.

- A researcher ethically hacking over 35 big tech firms via dependency hijacking.

- The SolarWinds supply-chain attack affecting upwards of 18,000 customers.

- Microsoft admits signing rootkit malware drivers with their code signing certificate.

- The compromised Codecov Bash Uploader in use by over 29,000 customers — Feds later suspected hundreds of customer networks were hacked.

- Enterprise password manager Passwordstate from Clickstudios delivered malicious updates.

And then there are examples of some foul play, in which attackers managed to successfully intervene with or pollute the upstream repositories to achieve their goal:

- Over 140 GitHub repositories that used the software workflow automation tool "GitHub Actions" saw malicious cryptomining code introduced by threat actors to automatically mine cryptocurrency using GitHub's servers.

- Microsoft's package manager WinGet was flooded with duplicate or corrupted packages overwriting existing ones.

- PyPI and GitHub successfully flooded with spam links on multiple occasions this year [1, 2].

As if these prominent supply chain attacks weren't enough, let's not forget 2021 is the year when the novel open source software (OSS) attack concept dubbed, "dependency hijacking," or namespace confusion rose to prominence.

By prominence, I mean, Sonatype has identified over 12,000 packages published to npm and PyPI alone — a vast majority of them being dependency hijacking candidates that received actual downloads.

And time and time again, Sonatype has discovered malicious typosquatting and brandjacking packages published to npm, PyPI that received hundreds, if not thousands of downloads.

All of this means, as far as distribution is concerned, the attackers found success.

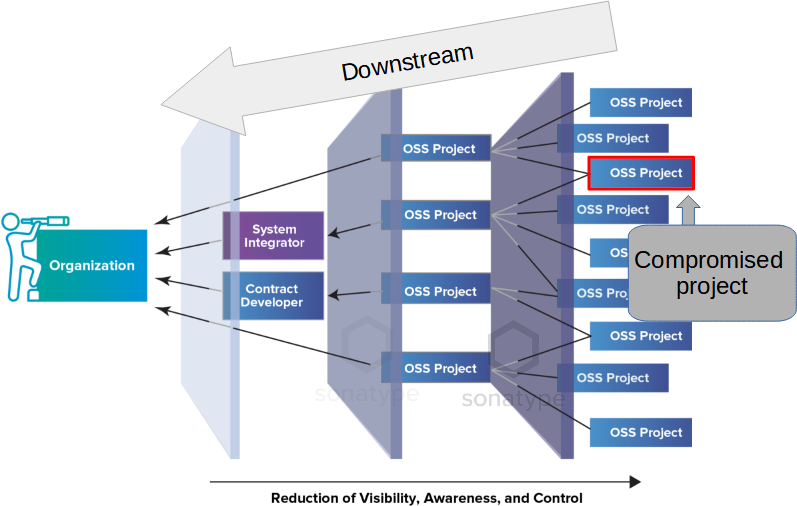

By interfering with the upstream codebase or repository, threat actors were able to successfully distribute their malicious code downstream. Hence, tampering with the supply chain process, regardless of extent or developers affected.

ENISA: "Not everything is a supply chain attack"

But, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) feels the term "software supply chain attack" is overused, and isn't quite convinced when it comes to what constitutes one.

In ENISA's report titled, Threat Landscape for Supply Chain Attacks, out last week, the agency thoroughly describes both the types and real-world examples of software supply chain attacks.

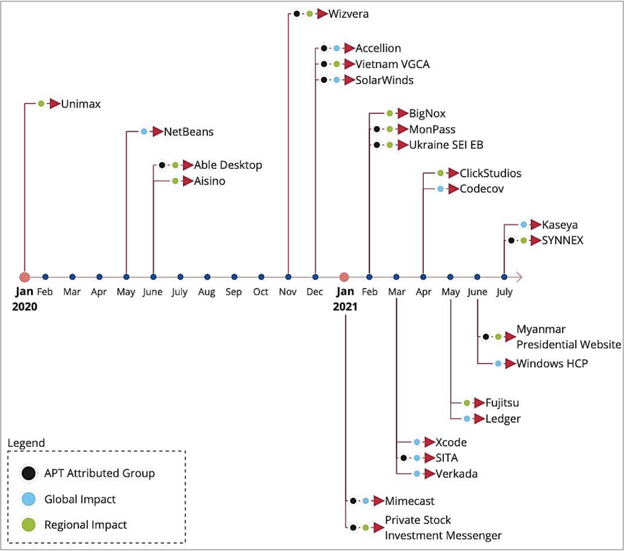

And, unsurprisingly, forecasts that 2021 may become the year we see four times the number of supply chain attacks seen in 2020. The timeline provided in ENISA's report is a clear testament to this increase:

Large scale supply chain attacks that resulted in concrete exploitation of noteworthy organizations and their assets were seen rapidly rising from the end of 2020 into this year.

But this part stood out to me:

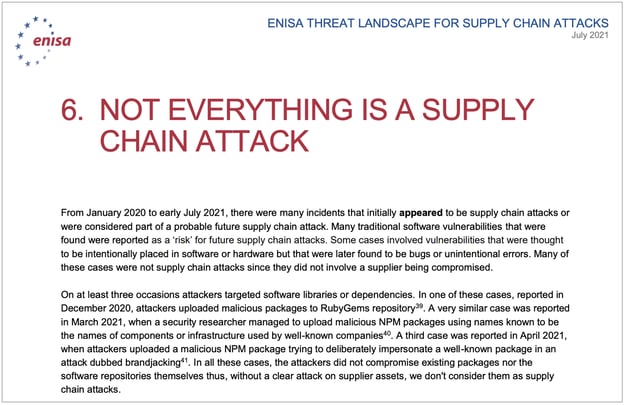

In the report section titled, "Not everything is a supply chain attack," ENISA has discounted many incidents that, although may not have led to a vast exploitation outcome, still consisted of attackers infiltrating upstream repositories with malicious intent or code.

So what is a supply chain attack?

As I explain in my CSO article, I believe a software supply chain attack covers any instance where an attacker interferes with any stage of the software "manufacturing" process or a software development life cycle (SDLC). Multiple consumers of the finished product or service are then negatively impacted.

This can happen when:

- Code libraries or individual components being used in a software build are tainted

- Software update binaries are trojanized

- Code-signing certificates are stolen

- A server hosting software-as-a-service (SaaS) is compromised

With any of these attacks, threat actors interject themselves either upstream or somewhere in the middle, to cast their malicious activities and their ill-effects downstream to many users.

As such, compared to an isolated security breach, successful supply chain attacks are a much bigger problem with a far-reaching impact.

ENISA, on the other hand, has a different take when referring to malware lurking in open source software registries:

"In all these cases, the attackers did not compromise existing packages nor the software repositories themselves thus, without a clear attack on supplier assets, we don't consider them as supply chain attacks," reads ENISA's report.

While I can see their point, I respectfully disagree. This definition does not take the full picture into account especially when talking about dependency confusion or some malware examples.

Supply chains are more than just production

As explained above, many such packages were distributed downstream with hundreds or thousands of downloads. For example, for the "amzn" malicious package alone we saw 300+ downloads.

Okay, but maybe this malicious dependency hijacking copycat never actually hit a production server, and was caught by us early on — it's totally plausible. But, that has clearly not been the case with Microsoft’s Halo game server, which was recently successfully hit by a dependency hijacking package.

It's important to remember that dependency hijacking or namespace confusion attacks occur automatically and without relying on a developer making a typographical error. This occurs as soon as a malicious dependency is pulled into the developer's build. Dismissing these incidents as not a software supply chain issue because they lack a major security outcome isn't wise.

The various examples listed above clearly demonstrate threat actors publishing malware or dependency confusion packages to an upstream software repository. In some cases, the attacks even pollute GitHub repos with bogus pull requests (often to mine cryptocurrency).

Why naming matters

Now, I've heard fair criticism by information security experts who frown upon the term "supply chain attack" being loosely used to define anything from a large-scale vulnerability exploit to a data breach.

But, what we are talking about here are not just theoretical examples of proof-of-concept research, but actual malware that has been successfully uploaded to open source software repositories. This problem is ongoing, with failures seen even today - malicious packages lurking on OSS repos and earning tens of thousands of downloads until they are caught.

Fortunately many of these attacks were caught early on and likely thwarted before they escalated into bigger incidents. However, that doesn't mean the integrity of software supply chains was not affected at some point, whether at the upstream or downstream level.

As far as naming goes, there definitely needs to be a line between what constitutes a supply chain attack and what doesn't.

For example, consider 50,000 vulnerable firewalls — all made by the same manufacturer exposing their passwords from threat actors exploiting a known vulnerability. This isn't a supply chain issue, as the manufacturing process itself wasn't tampered with.

But successful introduction of malware or malicious pull requests on software repositories that receive tangible distribution are incidents that can't easily be overlooked.

As soon as any form of successful tampering occurs in the software manufacturing or development process, putting the entire community at risk, so does a software supply chain attack.